words, words words

November 15, 2023

POLONIUS: What do you read, my lord?

HAMLET: Words, words, words.

Hamlet (2.2)

Dear Shining Saskatoon,

William Shakespeare was no stranger to words – as far as vocabulary goes, it’s safe to say that the Bard had an expansive one. For only receiving a rather minimal education (by his college-educated colleagues’ standards, anyways) Shakespeare’s deft ability to string a litany of words together to form perfect lines of iambic pentameter (a pattern in poetry where there are exactly ten syllables per line, with very specific alternating stressed and unstressed syllables) that also followed specific rhyme schemes is truly remarkable.

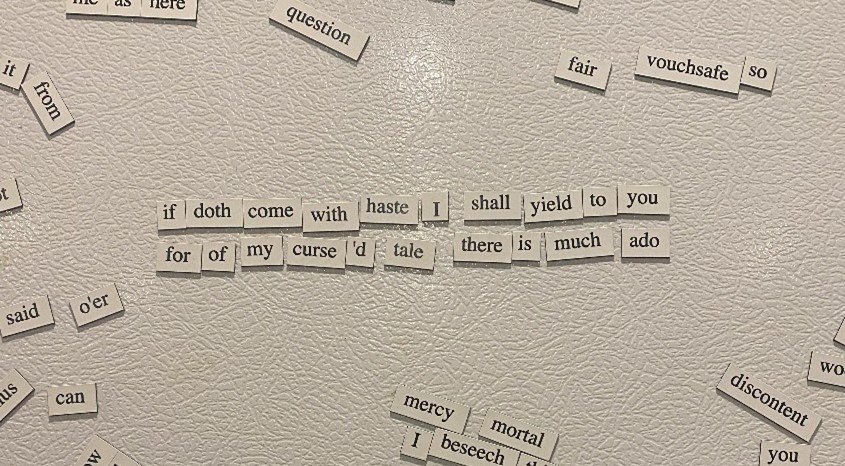

Or, so I was thinking this morning while waiting for my coffee to finish brewing in the Shakespeare on the Saskatchewan Admin Office kitchen. You see, someone from SOTS’s past purchased “Shakespearean Words” magnets – a bunch of simple, black and white words common in Shakespeare’s plays (think, “thy,” “forsworn,” “villain,” among others) that anyone with the desire or know how could fashion their own Shakespearean sentence from.

Well, I was standing in the office kitchen, staring blankly at these different words while the smell of fresh coffee filled the room and thought, “How the heck did Shakespeare do this 120,562 times when I can’t even make one line of iambic pentameter?”

I’m not kidding. Shakespeare wrote 154 sonnets to total 2,156 lines of poetry and 38 plays that total 118, 406 lines of text. That’s a lot of words.

You may not know this, but Shakespeare had to be the best. At the time, London’s theatre scene was cut-throat: not only was theatre banned within city limits, forcing theatres to be built in the more dangerous, crime-heavy and ungoverned areas outside of London while still being at the mercy to immediate cancellations and censorships by the Crown, but there were, at any given time, at least twenty other theatre groups that Shakespeare and his band of fellow actors had to compete with for audience members. Performing upwards of 6 nights a week, actors also realized early on that in order to maintain a business, outside patronage would be necessary. This led to the formation of ‘theatre groups’ that were often named after the group’s patron, and they would create and perform new theatre with this patron in mind. Of course, the more wealthy, noble, and upper class the patron, the better off your theatre group would be. And if you could outperform a different theatre company to sway the support of their wealthy patron to instead support your own? Well, all the better.

In 1594, Shakespeare joined the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, one of the most successful acting troupes in London. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men were even invited to perform for royalty, travelling from outside of the city with their costumes, sets, and actors to perform for Queen Elizabeth I and her court. It was worth it, though. Getting to perform in court decreased the likelihood of a play getting censored by the Crown while also guaranteeing the patronage of a number of wealthy members of the upper class. And there was a lot of wealth to go around: in one of his successful years as a playwright and actor for the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, it is estimated that Shakespeare would have made around 200 pounds – equivalent to the wage a skilled tradesman in Shakespeare’s time would receive for 4000 days of work, or enough to buy 24 horses, 107 cows, or 111 quarters of wheat. Such successful years hindered on the popularity of the performers and their plays and remaining in the good favour of the public, their patron, their Queen, and, later, after Queen Elizabeth’s death, the good favour of King James, the Scottish nephew of Queen Elizabeth. Theatre in Shakespeare’s time was lucrative, unsanctioned, and aggressively competitive.

In a dark, literary underworld of 17th-century London theatre, Shakespeare had to contend with the playwrights of other theatre companies, many of whom were college educated and received degrees from Oxford or Cambridge. Their schooling involved four years’ intense study of seven liberal arts (grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music), three kinds of philosophy (moral, natural, and metaphysical), as well as the study of Latin and Greek. Shakespeare, whose only education came from his childhood in grammar school memorizing texts and performing translations of Latin phrases almost entirely orally, was left to teach himself much of the ropes that came with playwrighting. Perhaps it was this lack of formal education that pushed Shakespeare to experiment and not be limited by the constraints of society. Or, perhaps, he just wanted to show everyone that he could do it. I can respect that.

Today, Shakespeare is credited with the invention of thousands of words by combining or manipulating Latin, French, and other roots, adding different suffixes and prefixes, and combining two or more familiar words together that his audiences would have understood their meanings given the context of the plays, (words like “birthplace” and “eyeball”). Shakespeare is also credited with inventing blank verse (lines of poetry with no set rhyme or metre) and popularizing iambic pentameter and the “English” or “Shakespearean” Sonnet (a sonnet made up of 14 lines that include three quatrains and one rhyming couplet).

With these words and his desire to question the status quo, Shakespeare pushed the boundaries of storytelling: he explored characterization, plot development, and genre to the point that many of his original themes, such as the prodigal son, the star-crossed lovers, the pitting of children against their parents, and plays based on true, historical stories, have influenced modern-day storytelling. How many movies in the last year would fall under one of these thematic categories? Almost all of them, I’d reckon.

Hold on…Yes! I got it! I finally made a rhyming couplet of iambic pentameter!

Shoot, but now my coffee is cold. I guess I’ll just have to make another.

Fair thee well,

From Fair Verona

For more resources and information on William Shakespeare’s influence on the English language, check out this following infographic from Maryville University.

Interested in just how William Shakespeare’s words have survived four centuries? We have the first folio to thank for that. Check out more information on the first folio here.