Shakespeare's First Folio

Celebrating the 400-year Anniversary of Shakespeare's First Published Folio

Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, also known as the First Folio, is a collection of William Shakespeare’s plays that was published in 1623 — seven years after the bard’s death in 1616 at the age of 52. The Folio contains 36 of Shakespeare’s plays, and an unbound copy in 1623 would have retailed for 15 shillings (about $255 in today’s dollars), whereas a copy bound in calfskin would have retailed for 1 pound (about $340 in today’s dollars). It is estimated that 750 copies were made. Out of those 750, there are only 235 known surviving copies.

It is currently regarded as one of the most influential books ever published, and is the most expensive work of literature ever auctioned. In 2020, a copy sold for $10 million.

How Was It Made?

There is a substantially large amount of work that goes into the creation of a book — especially in the 17th-century. While the Gutenberg printing press, invented by Johannes Gutenberg around 1436, made the process of mass-printing much easier than the creation of manuscripts (“manu” meaning “by hand” and “script” meaning “to write,” manuscripts were the main kinds of texts created in the medieval period. They were also exclusively religious texts, and were created, written, and illustrated by monks), there was still a lot of work to be done for those who wanted to preserve Shakespeare’s work. As such, there was a large cast of characters involved:

The Editors

John Heminges and Henry Condell, actors in the King’s Men Theatre Company (formerly the Lord Chamberlain’s Men Theatre Company) and friends of William Shakespeare, compiled and edited the 36 plays.

This would not have been as easy a feat as you think — as play scripts were not something that was readily shared with members of a theatre company, and if they were, actors would only get a censored script where only their role was included. This was due to the fact that the theatre scene in the 17th century was pretty cutthroat, and there weren’t the same kinds of copyright laws that we have today. It was common for other theatre companies to “steal” the plays of another.

Other times, there would be unauthorized publications of plays, and this would be done by either an audience member writing down the play as it was spoken or an actor or actors attempting to write down the play by memory after performing it — this is called ‘memorial reconstruction.’ These unauthorized publications were very wrong, with whole scenes being altered, characters forgotten, and dialogue misinterpreted. These would become to be known as “Bad Quartos” by modern-day scholars.

Heminges and Condell, then, had the difficult task of finding reputable copies of Shakespeare’s plays and editing those for publication. Once that happened, they enlisted the help of a Publishing Company to do the actual printing.

The Booksellers

Heminges and Condell teamed up with members of the Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers, a livery company in London that was formed in 1403, received a royal charter in 1557, and held a monopoly over the publishing industry in the 17th century.

These members were the booksellers, Edward Blount, William Jaggard and his son, Isaac. It is interested that Heminges and Condell chose to go with the Jaggards, as William had previously published unauthorized versions of Shakespeare’s plays while he was still alive — much to the offense of the playwright himself. In 1619, Jaggard had even tried to publish a collection of Shakespeare’s work in a single volume (much like what Heminges and Condell were undertaking themselves), but, again, did not have either the authorization to do so nor accurate and reputable copies to work from, and so this collection has gone down in history as the “False Folio.”

Regardless William Jaggard’s questionable professionalism, Heminges and Condell needed the space provided by Jaggard’s shop, and the finances the Stationers Company provided in the publishing process.

The Compositors

Next up in the book-making process was for Heminges and Condell to hand over their edited collection to the compositors.

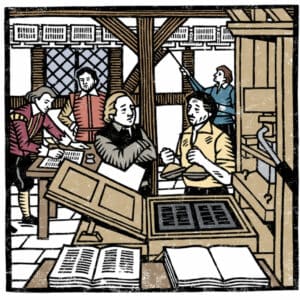

A printing press, very generally speaking, is a large mechanical device that applies pressure to an inked surface into a print medium (such as paper). In the case of the Folio, the inked surface is the letters of the play. In order to create books, printing shops had individual letters, called ‘type.’ Each letter was then arranged into words onto a hand-held ‘composing stick’ by a compositor. These composing sticks made up the lines of the text. Once enough of these lines were made to complete an entire sheet, they would be placed in a metal frame that would then be used for printing — one sheet at a time. The Jaggard printing shop, like all other printing shops in London at the time, only had enough type for a few pages. This means that after printing the amount of desired pages of a single page, the metal frame had to be opened, the type removed and cleaned, and then reused to make a different page.

The Jaggard Printing Shop employed at least five compositors who worked on the First Folio. Interestingly, every compositor has different spelling habits, unique typesetting habits, and levels of competence. Researchers have actually been able to distinguish which compositor worked on which pages — with one compositor, who worked on the least amount of pages, having extreme difficulties with spelling, grammar, and organizing the manuscript. It is theorized that this compositor is John Leason, a teenage apprentice at the printing press.

The Proofreader

It is possible that Edward Knight, the book-keeper and prompter of the King’s Men theatre company, was the proofreader of the manuscript sources for the First Folio. This would make a lot of sense, given that, as prompter, which is a very similar job to the modern-day stage manager, Knight would have had access to the full plays. There is evidence that many of the pages of the First Folio were edited and proofread as the large job of printing was already underway. Interestingly, because of the 17th-century printing process, each copy of the Folio differs in typographical errors. The typesetters would have fixed their own mistakes, for example, from previous copies as they saw and corrected typos, simple formatting mistakes, or incorrect placements of words/headings. It would have fallen on Knight, in conjunction with Condell and Heminge, to fix any problems in the manuscripts the typesetters were working from.

Did you Know?

There are many words and phrases that we still use today that are attributed to being invented by William Shakespeare. Isn’t that such a weird thing to be attributed with? The invention of a word? The English language is a West Germanic language that, in its earliest forms, was called “Old English” and is basically a distant language from what we speak today. In the 11th century, Middle English developed over 300 years from influences of Latin and French being incorporated into Old English. Then, Early Modern English began in the late 15th century. The biggest differences between Middle English and Early Modern English was the way vowels were pronounced (sometimes referred to as “The Great Vowel Shift), and the further incorporation of Latin and Greek words and roots into English.

It was in this time period that Shakespeare was writing, and so he had a lot of room to combine, create, and incorporate different roots, suffixes, and prefixes from different influential languages to form new English words.

Below, find an image created with 400 words that have been attributed to Shakespeare!

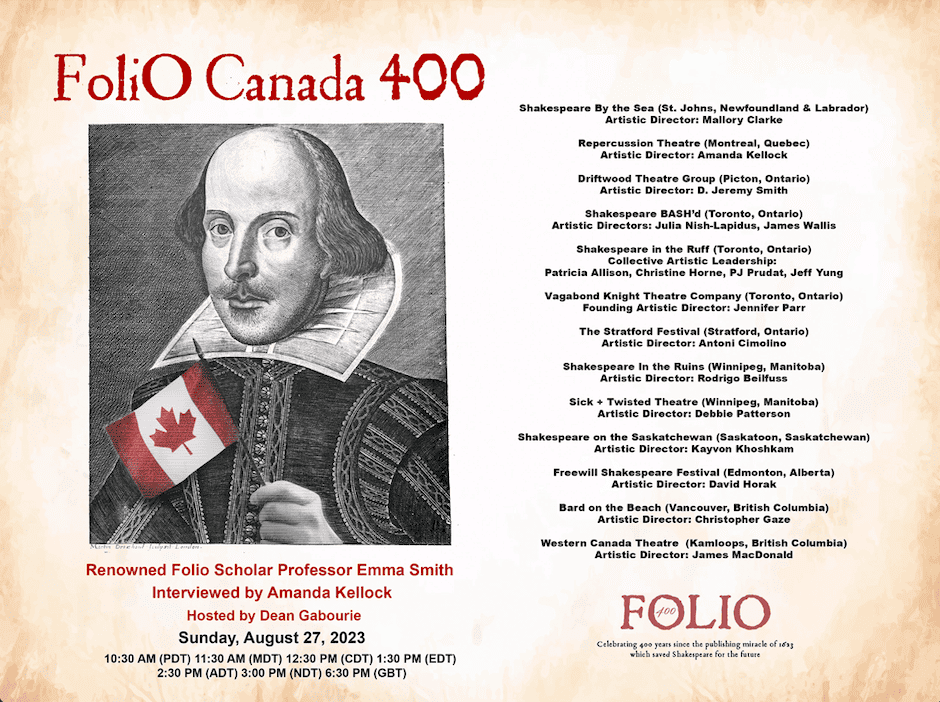

How is Canada Celebrating?

On August 27th, 2023, tune in to a conversation between Folio Scholar Professor Emma Smith, author of Shakespeare’s First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book! Interviewed by Amanda Kellock and hosted by Dean Gabourie, this event is supported by Shakespeare theatres from across Canada — including Shakespeare on the Saskatchewan! We would like to invite YOU, our patrons, our sponsors, our donors, and our friends to join us.

This interview is completely free to tune in to! Join us either on YouTube Live or on Facebook.

The FoliO Canada 400 event is a part of folio400, a global celebration of the 400th anniversary of the publication of the First Folio.

More Information

For more information, and to see how other theatre companies are celebrating 400 years of Shakespeare’s First Folio, visit folio400.com .

Find below illustrations from folio400’s website, including their art for As You Like It and Romeo and Juliet, the shows taking over our mainstage this summer! Make sure to check out their Contents page, which includes the approximate date all of the plays included in the First Folio was originally written, their routes to print, a brief synopsis of the plots, and spoken words from the First Folio!

h2 heading goes here

- Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Morbi in lacinia turpis.

- Nam posuere sagittis libero ut sagittis. Morbi nibh purus, rutrum vel pharetra id, convallis a orci.

- Sed sapien tellus, placerat at urna eget, tempus finibus mi.

- Mauris nisl augue, maximus vel ligula et, egestas sodales magna.

- Aliquam fermentum sodales diam feugiat consequat.

h3 sub-heading goes here

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Morbi in lacinia turpis. Nam posuere sagittis libero ut sagittis. Morbi nibh purus, rutrum vel pharetra id, convallis a orci. Sed sapien tellus, placerat at urna eget, tempus finibus mi. Mauris nisl augue, maximus vel ligula et, egestas sodales magna. Aliquam fermentum sodales diam feugiat consequat.

Ut in mauris id quam molestie ornare pulvinar at metus. Duis elit sapien, molestie mattis venenatis ac, pharetra a sem. Vivamus consectetur, magna vel tempus tempor, tellus risus tempor tellus, sed scelerisque ipsum nibh vitae tellus. Quisque vel laoreet tellus. Cras at enim at tellus convallis egestas. Mauris dapibus enim tortor, id ultricies erat porttitor non. Etiam turpis velit, mollis a posuere nec, dignissim in enim. Nunc at imperdiet mi. Vestibulum tempor lorem et neque placerat hendrerit. Nam sit amet urna eget orci fringilla vulputate a id quam.